Once, the tohorā prophesied that when humans arrived in Aotearoa they would cut down his brother the kauri tree to make their waka. Realising this, the tohorā travelled overland to plead that his brother join him beneath the waves. When the kauri refused, the tohorā offered his brother his skin in anticipation of the time kauri wood vessels would traverse the waters of Te Moananui o Toi te Huatahi.

In The Net, Ngahuia Harrison traces the long relationship between Ngātiwai and tohorā—a connection intertwined with complex histories of migration, economy, survival and resurgence. It also honours the teachings of tohunga Hori Parata, who, having restored traditional flensing practices for stranded whales, also revisited this ancient pūrakau at the outbreak of kauri dieback, leading to the creation of a rongoā derived from the tohorā’s body to help heal infected trees.

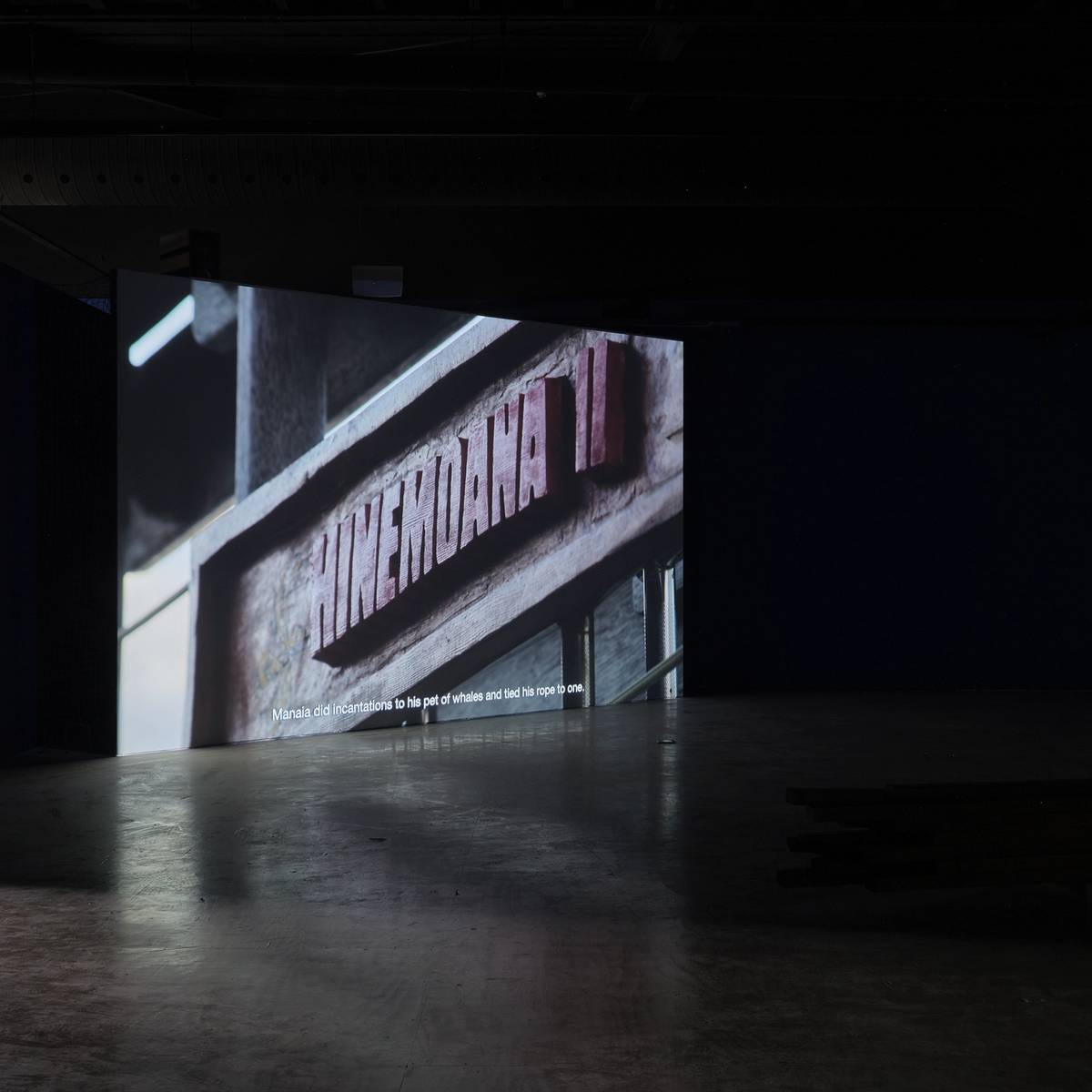

Ngātiwai’s ancestral relationship with whales has had strong practical and economic benefits. Two onshore whaling stations once operated in the rohe, one at Aotea and another at Whangamumu. The Whangamumu station was the only operation in the world known to have caught whales using nets. In this exhibition viewers will meet descendants of these whalers such as Eddie Cook, who still lives in the area today and operates an oyster farm.

The mātauranga gained through this historical linkage has long informed Ngātiwai’s ability to navigate new economies. The whaling industry, often considered solely a colonial enterprise, was in great part shaped by Indigenous labour, knowledge, and adaptability. Rather than something imposed by outsiders, for Māori whaling continued an unbroken practice of finding sustenance in the environment. Continued Māori participation in ocean-based industries, like Uncle Eddie’s oyster farm, demonstrates how economic engagement and ecological care can reinforce and support one another, rather than being locked in opposition. In contrast to Western conservation models that place people and nature at odds, Māori practices reflect a lived form of kaitiakitanga in which livelihood and environmentalism are deeply entangled.

This exhibition marks the first public presentation of Harrison’s broader research project titled Ngā Pōito i te Kupenga o Toi te Huatahi — The Netfloats in the Net of Toi te Huatahi. At its centre is the kupenga, or net—a metaphor for the moana as a connective structure, sustaining a people in their ancestral place. The pōito, Ngātiwai’s offshore islands, keep this net afloat. Understood in this way, the ocean is not a void between habitable zones but a lived space of interdependence and accountability. The Net resists the flattening of Māori experience into a single narrative, emphasising the polyvalent nature of the complex histories involved. Through photography, video, and archival material, it shows how Ngātiwaiknowledge continues to shape their relationships with the natural world, and asks the viewer to imagine an understanding of conservation that acknowledges its roots in both occupation and in traditions of coexistence, sustenance and intergenerational care.