“For every house is built by someone, but the builder of all things is God.”

Hebrews 3:4

The observation has often been made that the people of the Tai Tokerau were the first Māori to hear the gospel proclaimed, and the first to take up Christianity in its various forms. This is why one encounters so many houses of faith throughout the North, where almost every hapū built their own church or temple.

The first denomination to arrive was the Church of England—Te Hāhi Mihingare.

The famous haka “Te Hari a Ngāpuhi” was performed at Oihi by five hundred Māori in response to the sermon preached on Christmas Day, 1814, by Samuel Marsden. Pīhopa Te Kitohi Pikaahu, Pīhopa o Te Tai Tokerau gives the words of “Te Hari a Ngāpuhi,” with a translation by the late rangatira Sir James Henare, as follows:

“It is moving; it is shiftingIt is moving; it is shiftingLook to the open sea of WaitangiSpread before ulike the shining cuckooIt is good, all is wellChange is coming soon,it is on the horizonIt is good, all is well,let peace be established”

Next came the Methodists—Te Hāhi Wēteriana, when missionaries Samuel Leigh and William White established the first Wesleyan mission, Wesleydale, at Kaeo on the Whangaroa Harbour on 6 June, 1823. Under the leadership of the Reverend Nathaniel Turner, a mission was established a year later at Mangungu in the Hokianga. This mission baptised its first converts in 1830, and remains intact today. An ahurewa tapu, or sacred cairn of stones, stands upon the site of the first mission and was erected by Māori members of the Methodist Church under the guidance of the Rev A.J. Seamer.

Fifteen years later, the people of Hokianga witnessed the arrival of the Roman Catholic faith, brought by Bishop Jean-Baptiste Pompallier. Pīhopa Pomaparie marked his arrival with the celebration of the first traditional Latin Mass in New Zealand at Tōtara Point on 13 January, 1838, at the home of Thomas and Mary Poynton. He went on to win the affection of many Māori, speaking and writing Māori fluently. Pihopa Pomaparie later died in France, but his remains were exhumed and returned to Aotearoa by a delegation lead by the late Rev Dr Pā Henare Tate. The remains were interred beneath the altar of Hāta Maria Church, Motuti.

Following a vision on 8 November 1918, the Rātana Church founder Tahupōtiki Wiremu Rātana began his spiritual mission during that year’s influenza epidemic. By the early 1920s he had begun to successfully convert Māori from other denominations to the Rātana faith. Throughout the North, many Rātana temples can be observed in places such as Te Hāpua, Te Kao and Mangamuka. Each of these temples features the distinctive double towers common to Rātana temples, replicating those of Te Temepara Tapu o Ihoa at Rātana Pā.

Prominent also across the valleys and settlements of Tai Tokerau are a number of pristinely maintained Mormon temples, such as those seen in Pākanae and Te Horo. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, more commonly known as the Mormon Church, began their missionary activities amongst Māori in 1881. Many northern hapū and communities remain strongly Mormon to this day.

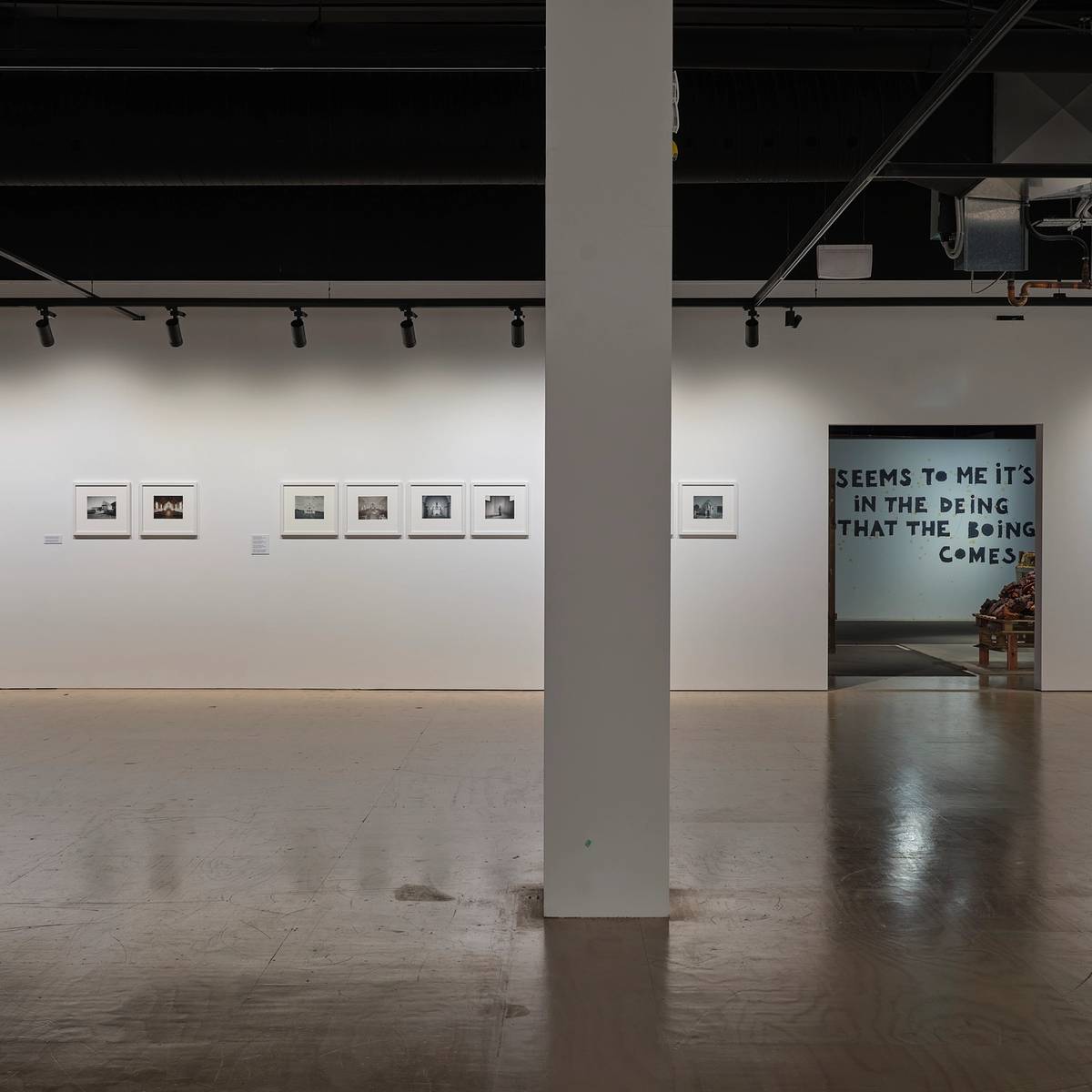

Laurence Aberhart’s photographs from the early 1980s beautifully capture the sacredness, stillness and solemnity of these magnificent places of worship and spiritual life, displaying their diversity of architectural form, liturgical tradition and layout. In the churches where the sacrament of Holy Communion or the Eucharist is celebrated, one can see the very prominent role played by the altar, while in churches whose congregation observe a stronger gospel preaching tradition, the pulpit is the central and most prominent fixture. Many Catholic, and some Anglican churches photographed have sought to incorporate traditional whakairo (carving) and tukutuku (woven panels). Some were built in the popular gothic style, replicating the churches of England and France. One particular church, Hato Kereti Hato Remehio in Waihou, was built in the Spanish mission style under the leadership of the German-Dutch Catholic priest Father Carl Kreymborg and Dame Whine Cooper.

In the Rātana temples, the whetū mārama (symbol of the star and moon) is prominently displayed as the central symbol of their faith. The Catholic churches display iconic liturgical symbols such as the crucifix, Italian statues of the Madonna and the patronal saints of the church and the central tabernacle containing the blessed sacrament. Many of the Anglican churches feature large shells used as baptismal fonts, detailed stained glass windows and often a richly embroidered banner of the Mothers’ Union organization.

All of these churches show the importance to the faith of those tupuna (ancestors) who sacrificed whenua (land), time, money, resources and labor for the construction and maintenance of these central spiritual community buildings. Many sit prominently atop hills within the grounds of urupū or wāhi tapu (burial grounds) so that they are visible from multiple locations within their valley, river or harbor communities. Many were put in places where the bell could be heard to toll, indicating the imminent beginning of a service, or conveying other important messages such as a death of a hapū member or the calling of a meeting.

Laurence Aberhart’s photographs beautifully display these churches without people inside them, allowing us to enjoy them as they exist when they are not occupied by hapū and communities on Sunday mornings, or during weddings or funerals, the most common uses of these buildings in some of these very rural and isolated communities. It is heartening to know that since the 1980s many have been lovingly renovated and restored for the enjoyment and spiritual growth of future hakatupuranga (generations).

These spectacular yet almost haunting photographs show these churches as they exist for most of the year. Still, silent, lonely, but loved.

“But the Lord is in His holy temple; let all the earth keep silence before Him.”

Habakkuk 2:20

Geremy Hema